by Pai Deetes, Phairin Sohsai and Tanya L. Roberts Davis

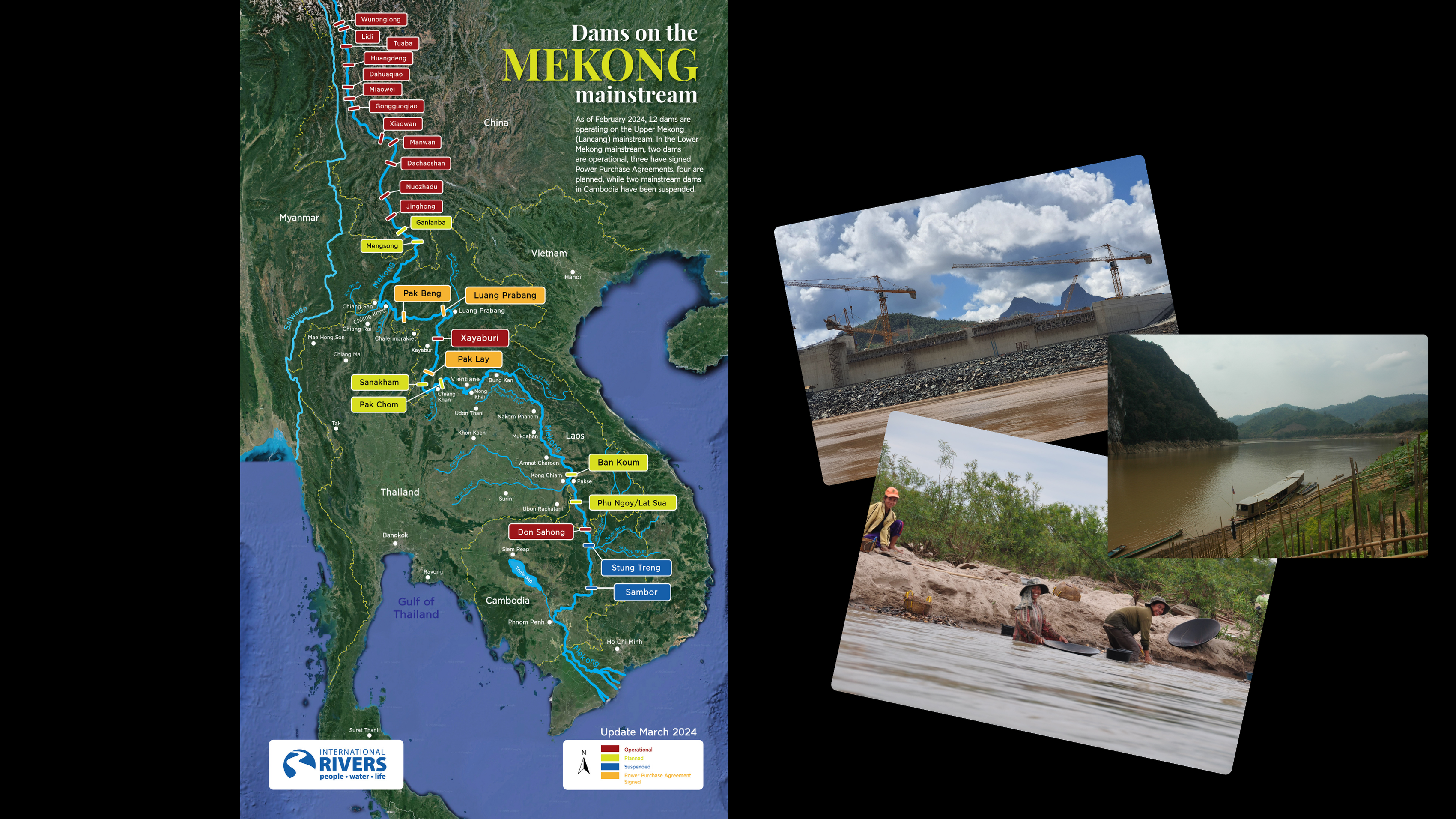

Today, International Rivers is releasing a map illustrating sites of struggle along the Mekong River where communities and allied civil society groups have been able to hold their ground —significantly delaying the planned development of destructive hydropower dams — and sacrifice zones where the build out of destructive hydropower dams has pushed ahead.

Despite consistent mobilization by riparian communities and civil society groups from the riverbanks to parliamentary, judicial and corporate arenas, along with submissions from Thailand’s National Human Rights Commission and National Ombudsman, the state-owned Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT) has taken the side of vested business interests by signing long term power purchase agreements (PPAs) with 3 new dam projects on the lower Mekong River mainstream: Luang Prabang (1,460 MW), Pak Lay (770 MW), and Pak Beng Hydropower Projects (912 MW). All projects will take several years to build before coming online. Given Thailand’s excess electricity supply, the burden will be borne by those living in Thailand, most especially residents in riparian areas nearest to the hydropower sites, but also in urban centers, where electricity prices are already rising. Combined with hydropower dams now becoming operational along the upper reaches of the Mekong — also known as the Lancang in China — devastating ecological, social and economic impacts are already felt by those living across all Mekong riparian states. To date, no comprehensive climate change assessments —with full lifecycle greenhouse gas accounting — are being undertaken on a project or cumulative basis, nor are impact assessments focusing on human rights and gender impacts underway.

In this context, collective attempts by community, environmental, social, economic and energy justice advocates to hold government bodies and project proponents accountable to the interests of the public are continuing apace — even though civic space is highly restricted, with trumped-up charges being lodged against rights defenders as a form of intimidation from those in powerful positions.

Impacts Already Being Seen and Felt by Riparian Communities: Damming of the Lancang

The damming of the Lancang has already disrupted the flow of sediments and water downstream to the Lower Mekong. Lancang cascade operations are leading to irregular fluctuations and even drying out of certain areas in the Lower Mekong Basin. This means that millions of riparian residents from Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam are all facing the consequences, ranging from declining fish catches, lack of predictable seasonal water levels and the loss of access to fertile sediment deposits along the riverbanks for growing rice and other subsistence crops. These challenges are also exacerbated by instances of climate change related extreme weather and slow onset events, including torrential downpours outside of the usual monsoon seasons, periods of drought and heat waves as well as riverbank erosion.

Pending Impacts from Projects with Signed Power Purchase Agreements

- Luang Prabang Hydropower Project (LPHP)

Sited 25 kilometers from the historic city of Luang Prabang in Northern Laos and a mere 4 kilometers from the Pak Ou Caves where ancient Buddhist shrines in reverence of the river have remained largely intact to date, the plans for this 1,460MW dam threaten the livelihoods of all who live in the surrounding area as well as an important UNESCO World Heritage Site. Concerningly, the project is also within an active earthquake zone (Loei / Dian Bian Fu Fault line). Yet, there is no clear emergency safety plan developed to deal with the risks if tremors were to result in any cracks, collapse or overtopping of the dam’s wall or associated structures. In fact, a UNESCO monitoring report published in April 2022 concluded that the project proponents as well as the Lao government should “take the precautionary approach, not to pursue the LPHP, and relocate the project.” Nevertheless, in November 2022, EGAT went ahead with signing a 35 year PPA, with scheduled power exports expected to begin in 2030. EGAT’s signing of the PPA in this context reveals an absolute lack of serious consideration of the social, cultural, economic, environmental harms, damages and losses that stand to result if the development of this project moves forward.

- Pak Lay Hydropower Project

This planned 770 MW dam is being built through a partnership between Thailand based-Gulf Energy Development PCL and China’s Sinohydro Corporation, sited around 70 kilometers downstream of Xayaburi dam and 200 kilometers from Chiang Khan in Thailand’s Loei Province. The development of the Pak Lay Dam is expected to lead to the direct dispossession of over 4,850 people, and affect up to approximately 82,000 people directly and indirectly. The PPA was signed on 20 March 2023 for 29 years with EGAT, the commercial operation scheduled for 2032. Commitments by the project proponents to take full responsibility for comprehensively restoring peoples’ livelihoods, as well as access to vital services, including water, sanitation, health and education remains lacking, as do meaningful commitments to be accountable for transboundary impacts to those living in Thailand.

- Pak Beng Hydropower Project

This proposed 912 MW dam is planned to be built by a subsidiary of China’s Datang Hydropower Company in partnership with Thailand’s Gulf Energy Development PCL, at a site approximately 97 kilometers from Thailand’s Chiang Rai Province. Despite the very real pending transboundary impacts, including potential irregular water level fluctuations, a loss of food security due to expected decreases in fish catches, and unknown levels of riverbank inundation, members of riparian communities in the area and local governing authorities have been left without any clear information about expected potential and cumulative impacts — even after seeking and requesting access to data. In September 2023, EGAT signed a 29 year PPA with commercial operation scheduled to begin in 2033.

Within two months, in November 2023, Thailand’s National Human Rights Commission issued a firm letter to the Thai Prime Minister, asserting the following: “It is the duty of the state to bring the concerns and perspectives of citizens into consideration before making any decisions that will impact the peace and well-being of people or communities. Therefore, we propose that the Thai government, represented by the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT), reconsider the signing of the power purchase agreement for the Pak Beng Hydropower Dam Project for the sake of protecting the human rights of Thai citizens.”

Possibilities to Avert Further Damage Remains: Sanakham and Phou Ngoy Hydropower Projects

The map also demonstrates that there are hydropower projects in the planning stages where Power Purchase Agreements have not yet been signed, meaning there is a window of opportunity to put the development of these sites on hold. This includes the Sanakham and Phou Ngoy Hydropower Projects.

The 684 MW proposed Sanakham Hydropower Project in Laos is planned to be developed by a subsidiary of China’s Datang International Power Generation Company and Thailand’s Gulf Energy Development PCL. The Sanakham dam site is located only two kilometers north of the Thai province of Loei. It is expected that the dam would compound the impacts of upstream and downstream hydropower projects, exacerbating the disruption of fish migration patterns, and block sediment that would flow downstream to retain the fertile river bank areas. It is also expected that the project would dispossess a total of close to 3,000 people from 13 villages in the surrounding areas.

In 2020, the Mekong River Commission (MRC) announced that the project would undergo the regional body’s Procedures for Notification, Prior Consultation, and Agreement (PNPCA). To date, there is no official confirmation on the completion of the PNPCA process. In the interim, given the range of impacts expected, local, regional and international civil society advocates have come together to urge the Thai government not to purchase power from the Sanakham Hydropower Project. Several of Thailand’s authorities have echoed the questions raised by civil society, having become increasingly aware of the clear pending impacts on Thai communities — particularly as a result of tireless campaigning efforts by riparian community members and their allies.

Significantly, in 2023, the Thai Government Ombudsman issued strong recommendations to the Prime Minister’s Office and other governmental bodies concerned following a thorough investigation of potential impacts of the Sanakham Dam. The report also included a retrospective consideration of the negative consequences to peoples’ livelihoods and the river ecologies already observed but without remedy due to the development of the Xayaburi Hydropower Project, as the first large-scale dam on the Lower Mekong River mainstream to become operational. These recommendations pointed out the serious harms done which cannot be simply remediated by one-time payments out to directly affected populations, the range of unknown consequences to local fisheries, riverbank erosion as well as severe water level fluctuations and sediment flows, the likelihood of inundation of lands used by residents of affected communities, the lack of any emergency plans to respond in case of operational failure or accidents and that other options for procuring energy, particularly from solar should be explored.

The Ombudsman also firmly called upon the Prime Minister along with the Cabinet and the Ministry of Energy to: “assess the balance between electricity demand and the various cross-border impacts that will arise from procuring electricity from dams in Lao PDR. This evaluation should consider the well-being of both the Thai and Lao PDR people residing along the Mekong River, taking into account various aspects. Specifically, it is recommended to delay the purchase of electricity from several projects, particularly the Sanakham Dam Hydroelectric Power Project situated in close proximity to the Thai border, as it may significantly affect Thailand. This impact includes security and cumulative cross-border effects on Mekong River resources, and economic and social impacts on Thai residents along the Mekong River.”

The proposed 778 MW Phou Ngoy Hydropower Project is planned to be built through a partnership between Thailand’s Charoen Energy and Water Asia Co. and the Lao Government, constructed by South Korea’s Doosan Heavy Industries & Construction and Korea Western Power. In this case, the MRC’s PNPCA process has not yet started. Although the Environmental Impact Assessment submitted by the project proponents to the MRC did acknowledge possible transboundary impacts, including inundation along the Mun River and implications for peoples’ livelihoods given expected losses to fisheries, the extent to which such impacts will create social and economic precarity for people living across the impacted areas remains to be fully considered. In particular, this is because the Phou Ngoy Dam is expected to lead to heightened water levels which would inundate riparian lands both along the Mun and Mekong River in Thailand, due to consequences of backwater flows. To date, such wide-ranging implications have not been considered in any publicly released project documentation. The reality is that critical information about potential transboundary impacts of the project, along with expected backwater flows, fisheries impacts, water level fluctuations, and planned discharges among other details, remain inaccessible to the general public, let alone local leaders, academics and concerned community members.

Significantly, the map also shows two proposed hydropower sites located within Cambodia – the Sambor and the Stung Treng Dams – as suspended. In March 2020, the Cambodian Government announced a ten year moratorium on the building of hydropower dams along the stretches of the Mekong River within its territorial boundaries. More recently, in late 2023, the Cambodian Prime Minister once again reaffirmed the commitment of the national government to avoid building dams on the mainstream Mekong, ensuring that to date, neither of these two projects will move forward in the near future. This instance stands as a clear testament to the concerted efforts of community rights defenders along with other civil society allies, journalists, academics and the scientific community working for over a decade to expose the harmful consequences that could be expected if these projects were ever to actually be built.

Recommendations for Moving Forward

Considering the impacts of each of these projects taken together — ranging from the economic burden that will be borne by the public in higher electricity costs; the years of construction before electricity will ever be generated; the unnecessary need for new power sources at this time given the high level of energy reserves in Thailand; along with the irreparable social, cultural, livelihood and environmental damages — there are better options for decentralized, localized ways of generating power. This is why, along with members of Fair Finance Thailand, ETO Watch Thailand and other allied coalitions, International Rivers urges both commercial banks and any international development financiers to:

- Stay away from offering loans, equity financing, bonds or other forms of assistance to this line up of yet-to-be completed destructive hydropower projects

- Prioritize support for expanding decentralized, locally appropriate energy solutions that meet the needs of under-served/marginalized areas within rural and urban centers for affordable, reliable, accessible electricity, such as rooftop and stacked solar options, and

- Commit to ensuring that decisions to provide financial backing for the energy and extractives sectors uphold all relevant international standards, including the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, the OECD Guidelines on Multinational Enterprises, and the Equator Principles, as well as emerging obligations related to the protecting space for public participation and the rights of future generations, such as the Maastricht Principles on the Human Rights of Future Generations.