How a battle over development on a California river helped inspire the founding of International Rivers and a global movement to amplify the voices of rivers and riverine communities.

By Kate Fried

Nearly 60 years ago, a self-described “awkward” teenager from Sacramento, California, named Mark Dubois, met the most powerful teacher of his life–the Stanislaus River. Mark’s relationship with the river and the influence of river defenders worldwide would ultimately help inspire the founding of International Rivers and galvanize a global movement to protect and celebrate our planet’s vital arteries and veins and challenge what Dubios refers to as “outdated neocolonial development models.”

The Significance of the Stanislaus River

Originating in the Sierra Nevada mountains and measuring 150 miles long, the Stanislaus snakes its way through five counties in Northern California before meeting its tributary, the San Joaquin River. For millennia, it has served as a source of fresh water for the verdant Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, once teeming with fish and wildlife.

A lifelong nature lover, Mark was drawn to the area’s beauty and the mysteries hiding within its abundant caves. Little could he have imagined the threatened Stanislaus would ultimately become a powerful symbol of the burgeoning environmental movement in the U.S. and inspire a global effort to amplify the voices of rivers and riverine communities.

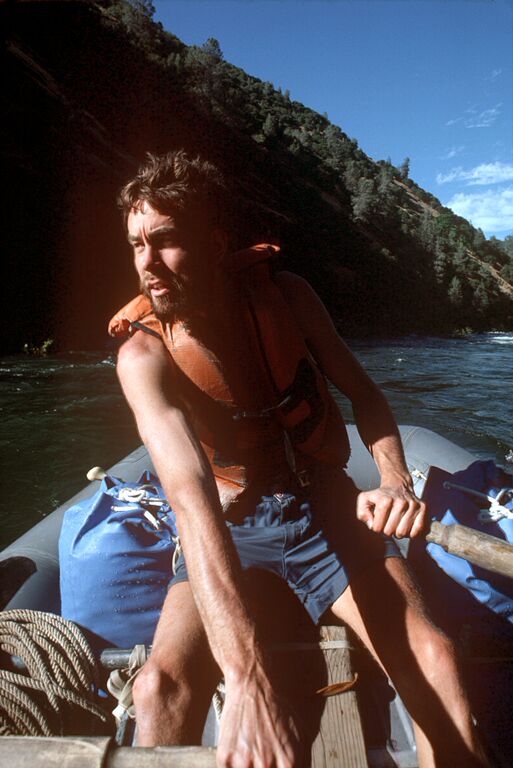

While the caves drew him to the Canyon’s “limestone majesty” in the late 1960s, by 1970 Mark became a commercial river guide. He and his friends soon started a group to share the magic of Stanislaus with urban youth. At the same time, a decades-long plan from an outdated development mindset to build the New Melones Dam for power and irrigation proceeded, just as America was waking to the ecological devastation of the dam-building era.

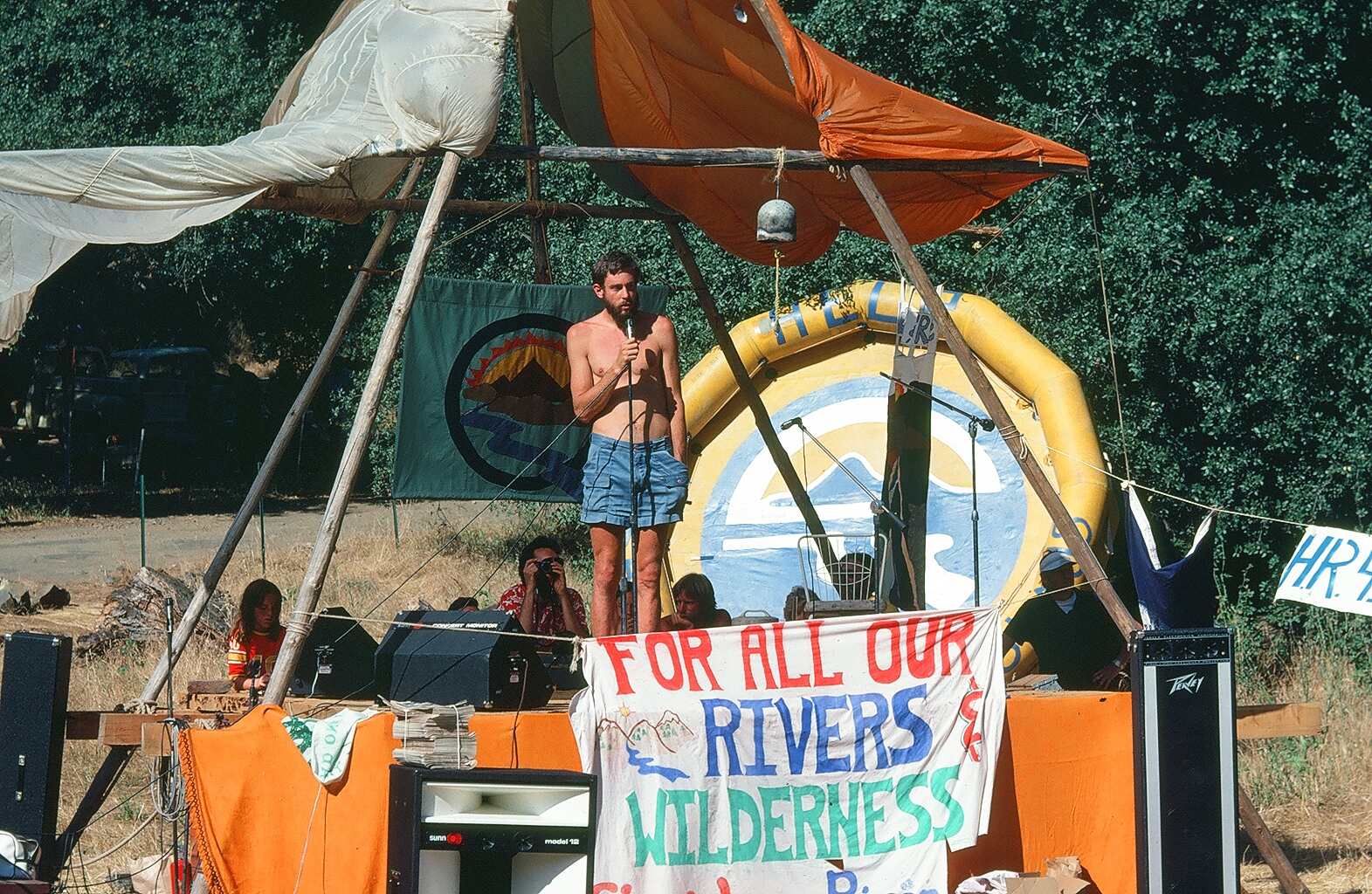

Mark slowly got involved in efforts to save the Stanislaus. By 1973, he joined Jerry Meral, David Kay, and the public relations team Roanoke to form Friends of the River (FOR) to speak for the river and oppose the project. For Mark, his deep love affair with the life of the river was teaching him about the antiquated paradigm behind large-scale development that only values nature when it’s extracted and converted into a commodity.

Protecting the Stanislaus

Over the next several years, FOR would launch a series of initiatives to save the Stanislaus, including a ballot initiative, court battles, and legislation. By then, California was starting to recognize the shifting values around water and withdrew the rights from the Bureau of Reclamation to fill the reservoir; the Bureau’s legal challenge went to the Supreme Court, which decided with California and for the river.

While conservationists’ efforts were initially unsuccessful, and New Melones Dam neared completion, Mark made headlines in 1979 when he chained himself to a rock in the Stanislaus Canyon to protest plans to drown the river. He stayed for a week, challenging the Army Corp of Engineers, who constructed the project, to drown him and all the life in the Canyon, as local authorities combed the area looking for him. He only agreed to unchain himself after the Governor’s office promised to monitor the river’s level. His actions forced a pause on the project and elevated concerns regarding hydropower to national prominence.

While the river was now gone, awareness of the need to protect rivers shifted. Three years later the Tuolumne River was protected, and three years after that, the Kings, Kern, and Merced were placed into the Wild and Scenic River System. While Mark lost the miracle of his beloved river, he gained a deep motivation to support humanity’s awakening to live with our rivers and natural systems.

A global “turn it off movement” is born

After losing his River, Mark married. He and his wife traveled throughout Asia and Africa. He had already learned that the West’s antiquated dam-building mentality had been exported overseas, even as the faulty economics and ecological devastation of dams were finally being exposed and their development nearly halted in the U.S. During these travels, he met local activists and received a tutorial on neo-colonial economics that indebt nations in exchange for their natural resources. From local water activists, he also learned that despite the good-sounding intention of foreign aid, money flows less to local communities and more to the Western companies installing dams.

In a recent interview with International Rivers, Mark explained that aid in areas such as Africa often goes to expensive dam projects that fail financially. “Money invested in water delivery [in the Global South] is actually a way to enrich U.S. and E.U. businesses,” he said. “The consequences to people are overlooked under the guise of development. Aid systems are not very well set up.”

Founding International Rivers

Earlier, the American environmentalist Huey Johnson had planted the seed of the need for an organization to help protect rivers globally. Mark’s experience meeting river defenders in the Global South further inspired the founding of International Rivers in 1983, initially called the International Rivers Network (IRN). Together with a small group of volunteers, Mark launched IRN to create an international network of activists working together to protect their rivers and communities, expose the absurdity of large-scale riverine development, and challenge extractive development models. Drummond Pike at the Tides Foundation supported the vision and provided initial seed funds to help launch the organization.

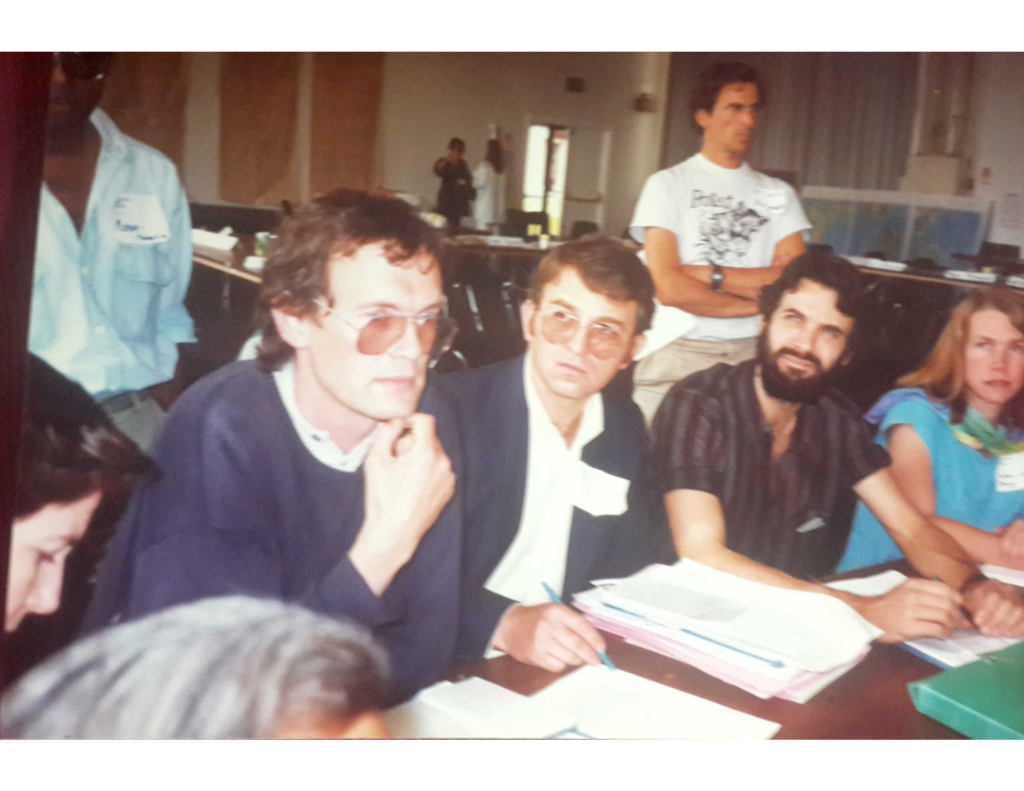

One early success was organizing the first international conference for river protectors in 1988. Seventy activists from 27 countries came together and learned from each other and the likes of scientist Amory Lovens about cost-effective development options, and witnessed first-hand the reality and drawbacks of California’s modern agro-business practices.

Throughout his life, Mark’s work has been inspired by the activism of leaders working to save their rivers. He credits fellow water warriors such as Anil Agarwal, founder of the Centre for Science and Environment in New Delhi and Kenyan political activist Wangari Maathai; Indian poet and activist Sugatha Kumari; fly fisherman Jorge Trucco, who halted several dams in Patagonia; Indian social activist Medha Patkar, who lead efforts to halt the massive Narmada Valley dam project; Vandana Shiva; International Rivers’ Monti Aguirre, and many others, for helping to spark the international movement to protect rivers.

The future of water activism

While its work was eventually successful in stopping dams and advocating for the rights of riverine communities, for Mark, the river rights movement is also about shifting mindsets. Mark observed, “We are conditioned to think we’re separate from Nature and to think we can’t make a difference. These inherited delusions have hurt the Earth for future generations and keep us small.” In many places, people hesitate to speak out about large-scale development altogether because they fear the repercussions of doing so.

In speaking for rivers and exposing the dam mindset, the movement also seeks a vastly more holistic approach to water so life is supported and a vibrant long-term economic model, rather than one based on “stealing from the future.” Mark points out that while water is currently valued as a commodity, it’s much more than that–it’s a sacred relative. He envisions a future where no one would dream of desecrating a river; because to do so is akin to harming your own mother. These days, he’s encouraged by emergent movements to recognize the rights of nature and rivers. “We’re at a time when we’ve done the best we can with old values,” he said. “We now get to find our voices to express the reality of what water truly is. As we learn to live with our sacred Earth, we all win, especially our children.”

Photos courtesy of Mark Dubois and International Rivers