By: Stephanie Jensen-Cormier, former China Program Director

With only three known individuals still alive, the Yangtze giant softshell turtle (Rafetus swinhoei) is the most endangered species of turtle in the world.

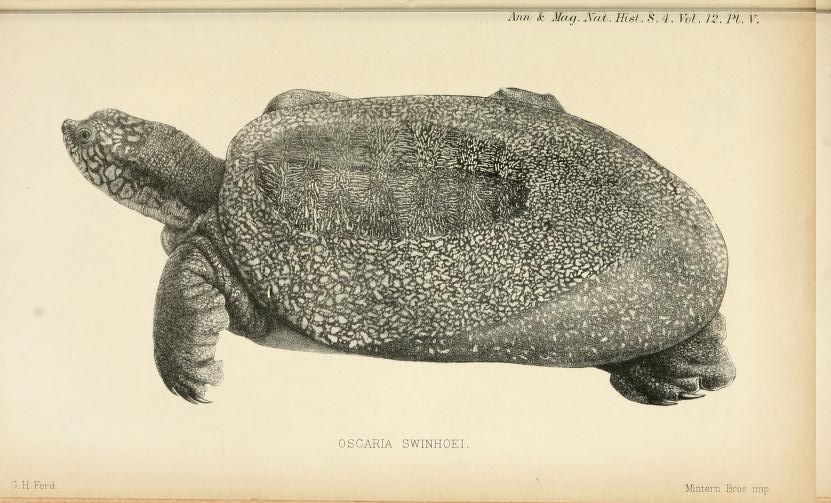

R. swinhoei is also the largest species of freshwater turtle in the world; it’s been recorded to reach sizes of over 39 inches in length and 28 inches in width and has a lifespan of up to 100 years in the wild. A turtle of this size can weigh between 155-220 pounds, and its unique physical attributes were certainly contributing factors to its population decline as it was deemed to be a source of food and an ingredient for traditional medicines. The turtle’s population has also declined because of the destruction of its natural habitats through increased rural development and dam construction.

R. swinhoei has been an integral part of the environment for many thousands of years. Ancient Chinese writings describe the giant turtles making their home in locations such as Lake Tai. Worshipped as symbols of good fortune, their undeniable uniqueness has made them a national icon. R. swinhoei has long been considered a sacred part of Vietnamese history, and the country as a whole mourned the death of the last remaining individual living in Hoan Kiem Lake in January of 2016. Despite its national importance, the cause of death remains unknown as scientists and other experts were denied permission to perform any post-mortem analyses due to the turtle’s revered status. The scientific community suspects that pollution in the lake and old age were the most likely causes of death.

Traditionally, the Yangtze giant softshell turtle inhabited the Yangtze River and Lake Tai, along with other areas in China and Vietnam. However, according to a survey conducted between 2013 and 2015, the last wild individual is reported to reside in Madushan Reservoir located along the Red River below Honghe in Yunnan Province, China. The two remaining individuals (a male and female) were placed into a captive breeding program in Suzhou Zoo in China in 2008.

Efforts to breed the remaining pair of R. swinhoei in captivity have so far remained unsuccessful. While the female has been reliably producing large clutches of eggs, they have all been infertile. Scientists attribute this to severe damage to the surviving male turtle’s shell and reproductive organs; they suspect the damage occurred during a fight with another male some time ago. Scientists have since attempted, on three separate occasions, to artificially inseminate the female. Instead of giving up, scientists continue to refine their technique by adopting new tools and practicing on other species of soft-shelled turtles.

Work by Dr. Steven Platt, a herpetologist for the Wildlife Conservation Society, and other scientists has centered on finding evidence of R. swinhoei in the wild. Most recently Dr. Platt, in collaboration with the Kunming Institute of Zoology, completed a survey of the Madushan Reservoir between the months of May and June of 2017. Survey methodology included baited fish stations, pedestrian patrols and interviews with local residents. Unfortunately, they discoverd no physical evidence of R. swinhoei. That said, Dr. Platt and his team suggest that the absence of unequivocal evidence (e.g., carcass) is cause to remain hopeful and that searching should continue until R. swinhoei is found or evidence to the contrary becomes available.

The negative impacts of large dam projects on species like R. swinhoei must not be understated. Wang Jian et al., (2013) reported that R. swinhoei prefers habitat in areas of confluence that include sandbars for sunbathing and egg deposition. Since the construction of the Madushan Hydropower Dam was completed in 2007, the downstream ecosystem has become dominated by extremely steep slopes which are unsuitable for sunbathing and egg deposition. Furthermore, these same steep banks have led to high levels of soil erosion and sediment deposition. Habitat destruction and fragmentation have separated already small and fragile populations. Scientists already know little about the geographic range of R. swinhoei, and therefore it’s important that we apply the precautionary principle. Saving the habitat of this turtle will benefit biodiversity in the region as well as the people who live there.

It’s difficult to not notice the disappearance of the largest freshwater turtle in the world. But there’s no doubt that many other species of flora and fauna in the Yangtze River Basin are suffering similar consequences due to the negative environmental impacts of dams.

We know that humans are intimately tied to the wellbeing of the land on which they live. This is even truer for rural communities who have survived on the bounty of these rivers and tributaries for generations. R. swinhoei is the canary in the coal mine for the region. If these environmental concerns go unaddressed and if dam construction continues, we will no doubt see a further decrease in regional biodiversity. The economic and social consequences for these dam-affected communities will continue to grow and those people who have the least amount of control over the decisions to alter their environment will continue to be the most negatively impacted.

The first step to rescuing this species is the successful reproduction of the two remaining turtles. The next step is adopting a new paradigm in the way that we relate ourselves with nature. We can no longer be separate from it but instead must see ourselves as part of it. Only then will the Yangtze giant softshell turtle have a home to return to.

Photo: The Yangtze Giant Turtle, Oscaria swinhoei; now known as Rafetus swinhoei. | Photo by JE Gray & GH Ford